Last Updated on July 26, 2024 by Mary Phagan

The Vigilance Committee of Mary Phagan stood guard for at least one day and one night at the tree from which they had hung Leo Frank, apparently expecting that someone—perhaps souvenir hunters or someone on the orders of Governor Harris, who had offered a reward for the conviction of any of the lynch party—might cut it down.

Two months after the lynching, a group climbed to the top of Stone Mountain, outside Atlanta, and burned a large cross. They say it was visible all over Atlanta.

On October 26, 1915, William J. Simmons, an ex-Methodist minister and a member of at least eight fraternal orders, gathered together thirty-four men, including members of the Vigilance Committee of Mary Phagan and three former Ku Klux Klan members, and signed an application to the State of Georgia to charter the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.

On November 25, Thanksgiving Day, Simmons again convened this group and they again ascended Stone Mountain and formally inaugurated the new Invisible Empire of the Ku Klux Klan. They again burned a large cross.

The original Ku Klux Klan, founded in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1867, was a secret society opposed to the Reconstruction policies of the radical Republican Congress and whose purpose was the re-establishment of white supremacy in the South. General N. B. Forrest, well known Confederate cavalry leader, was the first Grand Wizard of the Empire. The Empire immediately began a campaign of terror against ex-slaves and whites who involved themselves in black causes. They operated at night, their identities obliterated under white sheets. Their methods were flogging, torture, and lynching. They usually planted a burning cross on the property of someone whom they felt they had to threaten. It was their calling card.

As whites regained control of state governments in the South the Klan's power faded. In 1869 General Forrest ordered the abandonment of the Klan and resigned as Grand Wizard. But local organizations continued, some for many years.

The release, in 1915, of D. W. Griffith's "Birth of a Nation" further fueled the fires of the new Invisible Empire, which added to its motto of "white supremacy" anti-Catholicism and anti-Semitism. Its appeal, therefore, was wider than that of the original Klan. In the early 1920s, with the help of experienced promoters and fundraisers Edward Y. Clarke and Elizabeth Tyler, the Klan began exercising strong control over local politics throughout the South and spread rapidly into the North, especially Oregon, Oklahoma, Indiana, Maine, and Illinois. In 1922, 1924, and 1926, it elected many state officials and a number of Congressmen. At one point the Invisible Empire claimed a million members.

For ten years after its inauguration—or re-inauguration—the Klan exercised a career of terror. Then the death of another girl destroyed its power. In 1926, David C. Stephenson, who had ousted William Simmons from the leadership of the Klan and was at that time Imperial Wizard, was convicted of second-degree murder in the death of Madge Oberholtzer, whom, in consort with other Klansmen, he had kidnapped, raped, and abducted to Chicago from Irvington, Indiana. The case, which included some revolting perversions, created a widespread revulsion against the Ku Klux Klan. Throughout the 1930s its influence weakened irreparably. In 1944 it was formally dissolved.

Five years later, however, groups from six Southern states met to attempt to reform a national organization. During the Civil Rights era, the Klan again raised its head. It has never really died. It is recruiting members today. It recently attempted to involve my family.

In the months following the hanging of Leo Frank, August 17, 1915; it was alleged that there was a "mass exodus of Jews". The Alleged Jewish Exodus NEVER OCCURRED.

Daniel Boorstin

Joseph Boorstin, a distinguished historian who served as the Librarian of Congress for more than a decade, was born in Atlanta on October 1, 1914, to Dora Olsan and Samuel Aaron Boorstin, Russian- Jewish immigrants. His father was an attorney who served on Leo Frank's defense team. *After Frank's lynching in 1915, Boorstin's father moved his family to Tulsa, Oklahoma, in part to escape anti-Semitism. *Boorstin moved his family from Atlanta in 1917 two years after the lynching of Leo Frank. This again shows the manipulation of facts that Georgia Jews were victims of anti-Semitism and exodus of Jews occurred after the lynching.

Memo of Known Facts, October 12, 1953

American Jewish Archives

*Samuel Boorstin was former secretary to Governor John Slaton; practiced law in Atlanta from 1907 to 1917. Boorstin moved his family from Atlanta in 1917 two years after the lynching of Leo Frank. This shows the manipulation of facts that Georgia Jews were victims of anti-Semitism and exodus of Jews occurred after the lynching.

Memo of Known Facts, October 12, 1953

American Jewish Archives

Harry Golden, A Little Girl is Dead, 1965 wrote:

“By noon, all the Jewish businessmen had closed shop, and on the South Side people had sent their colored servants home. Jews locked their homes and, in the afternoon, began checking into the hotels, the Winecoff, the Kimball House, the Georgia Terrace, and the Piedmont. Many of the Jewish men took their families to the railroad station and sent their wives and children to relatives outside the state.”

On January 5, 2021, the noted presidential historian Michael Beschloss, tweeted the false and thoroughly debunked fiction that Jews fled the state of Georgia as a result of the lynching of Leo Frank on August 17, 1915.

There is no evidence of this alleged exodus and none of the serious historians of Jewish history will back the claim.

Several notable scholars correct Beschloss

on that issue:

Strangers within the Gate City: The Jews of Atlanta, 1845-1915 (Philadelphia, 1978)

Steven Hertzberg

Page 213:

“Harry Golden has written that all Jewish businessmen closed shop, locked their homes, and checked into hotels, most remaining for several days. However, while Jews undoubtedly preferred the safety of hotel rooms and a few send their families out of the state, there was no dramatic exodus or panic. The Jews were frightened, but most went about their business as usual, and no serious incidents occurred.”

The Jew Accused, 1991

Albert S. Lindemann

Page 270:

“Earlier accounts of this period, particularly Golden’s A Little Girl is Dead, presented a picture of Jewish panic, of exodus from the city but a more recent and careful scholar [Hertzberg] has concluded that ‘there was no dramatic exodus or panic [Jews]. The Jews were frightened, but most went about their business as usual and no serious incidents occurred.”

Page 275:

“Even when is Atlanta, where the Jewish community was deeply shaken by the Frank Affair and where Jewish leaders long opposed efforts to rehabilitate Frank because of the hostility such efforts might revive, Jews continued to move into the city in numbers no less impressive than before the Frank Affair.”

Page 217:

“From 4,000 in 1910, the Jewish population rose to 10,000 in 1948, 16,500 in 1968, and 21,000 in 1976.”

Institute of Southern Jewish Life Study

Goldring/Woldenberg, 2006

http://www.isjl.org/history/archive/ga/atlanta.html

“The Community Grows

Despite the fears stemming from the Frank lynching, Atlanta’s Jewish community continued to grow. In 1910 there had been 4,000 Jews, by 1937 there were 12,000.”

The Secret Relationship Between

Blacks & Jews, 2016; Vol. 3

“This claim is patently false. The only Jewish exodus from Georgia occurred in 1740, when England banned slavery there. According to historian RabbiJacob R. Marcus, Jews left because ‘Negro slavery was prohibited, the liquor traffic was forbidden.’”

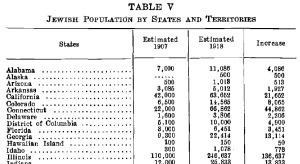

1921 Jewish Year Book

This chart shows a Jewish population

INCREASE in Georgia of 13,114!

Those who remained—and particularly those in Atlanta—were financially crippled by a huge boycott of Jewish businesses. The Jewish community, or at least some of its more prominent members, had felt, in fact, an increasing anti-Semitism for the previous three decades or so. This feeling mounted as resentment of the monies which poured in from Jewish organizations around the country—particularly in the North—to aid in Leo Frank's defense and subsequent appeals soared.

Mary Phagan's death and Leo Frank's hanging gave impetus to the formation of the Anti-Defamation League of B'nai B'rith.

At the time of his arrest, Leo Frank was president of the Atlanta chapter of B'nai B'rith, the Jewish fraternal order which had been founded in 1843. There were plans for the organization of its Anti-Defamation League, to combat anti-Semitism in the United States and "to work for equality of opportunity for all Americans in our time," as their charter reads, but it took the condemnation of Leo Frank to galvanize it into being. The League was established four weeks after Leo Frank's trial ended. As Dave Schary, the fourth national chairman of the League has stated, "Certainly the B'nai B'rith would have founded the League sooner or later, but the story of Leo Frank struck the American Jewish community like nothing be-fore in its experience. It was Frank's destiny to give the League a sense of urgency that characterizes its operations to this day."

At the founding ceremonies of the League, Adolph Kraus, then national president of B'nai B'rith, commenting on the widespread prejudice and discrimination, said:

Remarkable as it is, this condition has gone so far as to manifest itself recently in an attempt to influence courts of law where a Jew happened to be a party to the litigation. This symptom, standing by itself, while contemptible, would not constitute a menace, but forming as it does but one incident in a continuing chain of occasions of discrimination, it demands organized and systematic effort on behalf of all right-thinking Americans to put a stop to this most pernicious and un-American tendency.

The Anti-Defamation League practically from its inception vigorously opposed all lynchings. It, along with the NAACP, works to correct falsehoods in all forms of media and to distribute information correcting misconceptions about Judaism. It owes its genesis to Leo Frank. And to Mary Phagan.

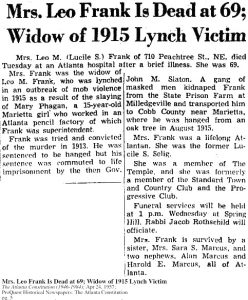

After Leo Frank's death, Lucile Frank became a pillar of the Atlanta Jewish community. She worked in one of the better women's clothing shops, never remarried, and until she died, in 1957, signed all her checks and papers "Mrs. Leo M. Frank." Her will specifically expressed that she not be buried in New York next to Leo Frank and that she be cremated. [historyatlanta.com > lucille-frank].This fact is something Leo Frank's activist defenders do not wish to highlight in their efforts to bias our understanding of these related events

The Obituary of Lucille Selig (1888 - 1957) the wife of Leo Frank, published in Georgia's AC on Wednesday, April 24th, 1957.

The Obituary of Lucille Selig (1888 - 1957) the wife of Leo Frank, published in Georgia's AC on Wednesday, April 24th, 1957.Tom Watson was indicted and tried in the United States District Court for sending obscene matter through the mail and was acquitted in 1916. Initially he supported Hugh Dorsey in the gubernatorial race. Dorsey won and remained governor of Georgia until 1921. In 1920 Dorsey ran for the United States Senate, but Watson himself ran and won. Two years later he died from a bronchial attack. One of the memorials on his grave was a cross, eight feet high, made of roses. The Ku Klux Klan had sent it.

Jim Conley served less than a year of his sentence on a chain gang.

Some months after that, he was convicted of breaking and entering a business establishment in the vicinity of the Fulton County courthouse, and was sentenced to twenty years' imprisonment, which he served. It was after that that he and my grandfather and my aunt had the famous (in our family) conversation about little Mary Phagan. Then he apparently disappeared. In 1941 he was among a group picked up for gambling by the Atlanta police.

In 1947 he was again arrested—on a charge of drunkenness.

He died in 1962. Rumors of a deathbed confession of his having killed Mary Phagan have grown increasingly more persistent.

Did Jim Conley give a deathbed confession?

On April 6, 1987 my father and I spoke with three members of the Anti-Defamation League—Stuart Lewengrub, Regional Director of the Southeast Office; Betty Canter, Assistant Regional Director of the Southeast Office; and Charles Wittgenstein, Counsel for the Southeast Office. The League, we felt, would certainly have tracked down and confirmed this rumor. All three were emphatic: the rumor had no basis in truth.

Publications, films and plays concerning the Mary Phagan-Leo Frank case began even before Leo Frank was hung:

1913-1914-Georgia Reports, Supreme Court of the State of Georgia at the October Term, 1913, and march Term.,1914. Volume 141, Stevens & Graham

1914—The Frank Case: Inside Story of Georgia's Murder, published by Atlanta Publishing Company. Argument of Hugh Dorsey, Solicitor for Fulton County, published.

1915—C. P. Connolly reported the trial in Collier's Weekly and then published a book, The Truth About the Frank Case.

1922—The French journalist, Van Paassen, claims that the teeth marks on Mary Phagan's head and shoulders do not match the X-rays of Leo Frank's teeth. He publishes his findings in the book, To Number Our Days, in 1964.

1936—Death in the Deep South by Ward Greene published.

1937—"They Won't Forget," a movie based on Ward Greene's novel and starring Lana Turner as little Mary Clay appears.

1938—Tom Watson: Agrarian Rebel by C. Vann Woodward published.

1943—I Can Go Home Again by Arthur Powell published.

1952—Guilty or Not Guilty by Francis X. Busch published.

1956—Night Fell on Georgia by Charles and Louise Samuels published.

1959—Confessions of a Criminal Lawyer by Allen Lumpkin Henson published.

1962—"Profile in Courage" series is aired by NBC. One deals with John M. Slaton.

1965—A Little Girl is Dead by Harry Golden published.

1967—A five-part series on the trial appears in the Atlanta Constitution, and the play, "Night Witch" has a short run.

1968—The Leo Frank Case by Leonard Dinnerstein published, reissued in 1987,1991, 2008

1986- Fiddlin" Georgia Crazy: Fiddlin" John Carson, His Real World,and the World of His Songs, Gene Wiggins

1987 -Mary Phagan, The Murder of Little Mary Phagan

1988-Robert Seitz Frey and Nancy Thompson-Frey, The Silent and the Damned: The Murder of Mary Phagan and the Lynching of Leo Frank

1991-Albert S. Lindemann, The Jew Accused

1997-David Mamet, The Old Religion

2000-Jeffrey Melnick, Black-Jewish Relations on Trial: Leo Frank and Jim Conley in the New South

2003-Steve Oney, And the Dead Shall Rise: The Murder of Mary Phagan and the Lynching of Leo Frank

2008-Leonard Dinnerstein, The Leo Frank Case, reissue

- Chapter 1 - "ARE YOU, BY ANY CHANCE...?" Final [Last Updated On: July 24th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2021]

- Chapter 2 - The Legacy Final [Last Updated On: August 14th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2021]

- Chapter 3 - My Search Begins Final [Last Updated On: July 25th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2021]

- Chapter 4 - The Case for the Prosecution Final [Last Updated On: October 11th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2021]

- Chapter 5 - The Case For The Defense Final [Last Updated On: October 13th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2021]

- Chapter 6 - Sentencing And Aftermath Final [Last Updated On: October 7th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2021]

- Chapter 7 - The Commutation Final [Last Updated On: July 26th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2021]

- Chapter 8 - The Lynching Final [Last Updated On: October 10th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2021]

- Chapter 10 - Alonzo Mann's Testimony Final [Last Updated On: July 26th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2021]

- Chapter 11 - The Phagans Break Their Vow Of Silence Final [Last Updated On: July 26th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2021]

- Afterward - Pardon: 1986 Final [Last Updated On: July 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2021]

- Chapter 12 - Application For Pardon, 1983 Final [Last Updated On: July 26th, 2024] [Originally Added On: June 1st, 2023]

- Chapter 14: 1989: ADL Attorney Dale Schwartz Revisionism of Judge Roan Statement to Jury Final st of Judge Roan's Charge to Jury Final [Last Updated On: July 28th, 2024] [Originally Added On: October 16th, 2023]

- Selected Bibliography: Final [Last Updated On: October 11th, 2024] [Originally Added On: December 25th, 2023]

- Index: Final [Last Updated On: October 11th, 2024] [Originally Added On: January 1st, 2024]